The sun is up and everyone is here for breakfast. I learned that to be comfortable the birds want proximity to trees. That’s not a surprise, but never having considered it—and having a human orientation—it never occurred to me that the availability of food would not overcome concerns about a tree perch to get back to. Seems it doesn’t. What to do? Off to the woods to find a portable forest (or tree branch jungle gym) for the deck.

The sun is up and everyone is here for breakfast. I learned that to be comfortable the birds want proximity to trees. That’s not a surprise, but never having considered it—and having a human orientation—it never occurred to me that the availability of food would not overcome concerns about a tree perch to get back to. Seems it doesn’t. What to do? Off to the woods to find a portable forest (or tree branch jungle gym) for the deck.

The songbirds are just making their way to familiarity while the hummers have settled in. This little beauty sits on her branch opposite the kitchen window and makes kitchen chores a pure delight.

The songbirds are just making their way to familiarity while the hummers have settled in. This little beauty sits on her branch opposite the kitchen window and makes kitchen chores a pure delight.

One of my top one hundred things I love about Awareness Practice is that there’s always something to learn, something new to see, or at least a new way to see something old. (Some of you probably remember the “Learning to Love Learning” fixation of a while back, the one that never became a book and has perhaps found the persons eager to write it.) “What now?” seems a logical question for us when we’re more interested in presence than in reviewing tired old stories and “knowledge” from the past. Curiosity may have killed the cat but it certainly makes for a fascinating life for a human. However… it does come with some painful moments along the “learning” curve.

When everything I read backed up the lovely chap at the bird store letting me know that suet is really helpful in getting our little feathered friends through the winter, I happily grabbed up a couple of packages. As a decades long vegetarian I had never heard of suet, or if I had, it didn’t get the benefit of any of that vaunted curiosity. Profound apologies, a proper burial, and a prayer of thanksgiving have followed.

The good news brought by this foray into the cost of ignorance is that I can spread unsalted peanut butter on their jungle gym, they will be just as provided for, and no one has to die. Turns out they enjoy a lot of the same foods we enjoy. What they shouldn’t have is avocado, caffeine, chocolate, salt, fruit pits and apple seeds, onions, garlic and Xylitol. Also in that list is “fat.” Go figure!

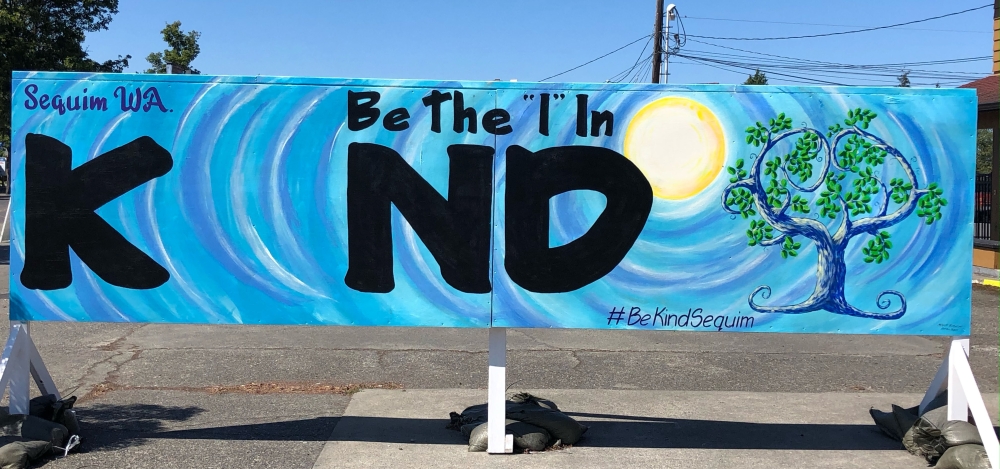

On the way to town to get peanut butter, I had a visual reminder of this whole process. During the warm months on the main corner of town (Sequim Avenue and Washington Street) there’s a huge sign depicting the town motto: Be the “I” in KIND. During the rest of the year, smaller versions of it remain on the street lights. Good reminder for us that there is always a choice that is most compassionate for all!